Save me from myself

Save me from myself

22 March, 2017 •Exploring the disconnect between providers and consumers of savings products in Zambia

“Yes, I do save. I have a bank account in Kabwe, two hours away.”

“Why so far away when there are banks here in Chisamba?”

“It keeps me disciplined! I know that if I have to travel two hours to make a withdrawal from my bank account, I will not squander the money.”

The above exchange between a female farmer and an interviewer was captured during the qualitative research for the Making Access Possible (MAP) study in Zambia. Although it may sound like an uncommon practice, we found this is not out of the ordinary. There are numerous examples of individuals in Zambia who create this type of friction to help them keep their money saved.

For example, a self-employed man in his early twenties revealed that he had a “Baby Savings” account with a Zambian commercial bank, Zanaco, despite not having a baby. His reason? He was preparing in advance. Another young man, employed in the private sector in Zambia, saves part of his salary in a savings account in Canada through his Canadian-based employer. When asked why he did not save with a bank at better interest rates, he explained that when his family asks him for money he could not honestly say no if he had access to it. By saving with his employer he could truthfully say that he did not have access to that money and could keep his money saved for his goal of purchasing a car.

This concept of friction in financial inclusion was originally identified by Ignacio Mas. Mas found that behaviour, which often seemed irrational for formal providers, was perfectly rational for consumers as it helped them keep their money saved.

In Zambia, this disconnect between how consumers behave and how formal providers think they should behave has resulted in savings products that remain largely unused. Formal providers blame this on a lack of savings culture, but upon further examination, we observe that Zambians do save at high levels, but that many savings products do not meet their savings needs.

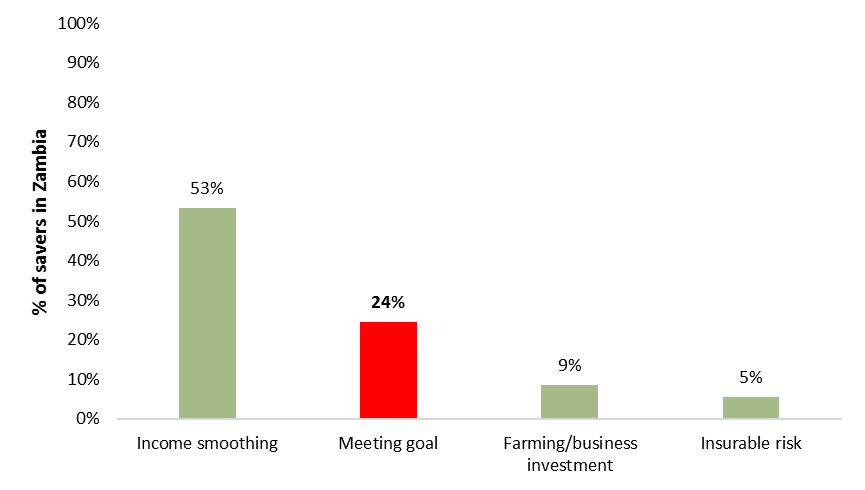

FinScope (2015) reveals that two-thirds of Zambian adults save. Figure 1 below shows that much savings is to smooth income to meet living expenses or manage non-medical emergencies. What is surprising is the proportion of adults that are saving to meet a specific goal: paying for school/university fees, building a home, buying land, or accumulating assets. This requires adults to keep their money saved over time, yet few providers are meeting this need. Most adults in Zambia (70%) use informal mechanisms such as Chilimbas, Savings Groups, family and friends or the proverbial mattress to save for these purposes.

The findings from FinScope and MAP confirm that Zambians do not need to be sold on the benefits of savings. They already save at a high rate, but prefer products that are either easy to access to smooth income when needed or create friction for them when trying to keep their money saved for longer periods of time. Most banks do not offer products with the latter in mind (and some, like our female farmer, invent them). Moreover, formal savings accounts come at relatively high fees given the small sums being saved, sometimes constituting multiple months of savings contributions.

Informal services such as Chilimbas and Savings Groups are popular amongst Zambians when needing to save for longer periods of time. This is because such methods create friction for savers by incorporating commitment devices and a fixed period where you cannot access your money. These products speak to the saving needs of clients.

So, what can providers do?

Take, for example, the baby savings accounts. Even though this is a savings account like any other, by giving it a specific name, it creates a target in the consumer’s mind which reflects how people already think. Mas finds that people perform mental accounting by compartmentalising different incomes in their minds. Having a savings account named after the goal encourages savings behaviour.

Or take the example of the young man saving with his employer. The impact and effectiveness of embedding features like this that drive commitment to savings have been well documented in academic research, particularly when those savings are earmarked for a specific purpose.

Formal providers should try to mimic this behaviour in product design. For example, offer a targeted commitment savings account with a fixed term that prevents the account holder from drawing on funds over a fixed period. If the savings account is targeted for a specific purpose and named accordingly, such as an educational savings account or a baby savings account, this can also help clients to keep their money saved.

Research conducted in Malawi finds that smallholder cash crop farmers with commitment savings accounts had significantly more deposits in their savings accounts. They were more likely to spend money on agricultural inputs than those who had savings accounts without these features. The authors believe the accounts were effective because these additional features meant that funds were kept from the account holder’s social network. When family members came around asking for money, the farmers could not draw on these funds even if they wanted to.

The lack of a savings culture in Zambia is a regularly cited issue by formal providers and suggests that there is a disconnect between consumers’ needs and formal providers’ understanding of how to meet them. Ordinary consumers display prevalent savings behaviour and a need for long-term savings to meet their goals. In Zambia — like in many other countries — owning a home, sending children to university, or saving up for one’s first child are real, tangible goals for consumers. If formal providers are serious about financial inclusion, they will design products that help consumers achieve this. If not, the consumer will continue to find other ways to save.