Secure in Exclusion

Secure in Exclusion

7 March, 2016 •Opening a bank account in South Africa can be a frustrating experience. First, you need to pull together an inventory of documents (proof of income, employment and address, national identity, passport, etc.), second, you need to book time off work or make provision for an early Saturday (when banks operate), then you need to physically go to the Bank, wait in the queue, and hope that the Banks’ processes and systems will agree that you are in fact who you say you are. Hopefully, this only takes one trip. More likely, it will be multiple trips. For example when a document is mislabelled or, more commonly, when you and the Bank have a different view on what an “authentic” document is.

Early warning signs of a less inclusive financial sector in South Africa

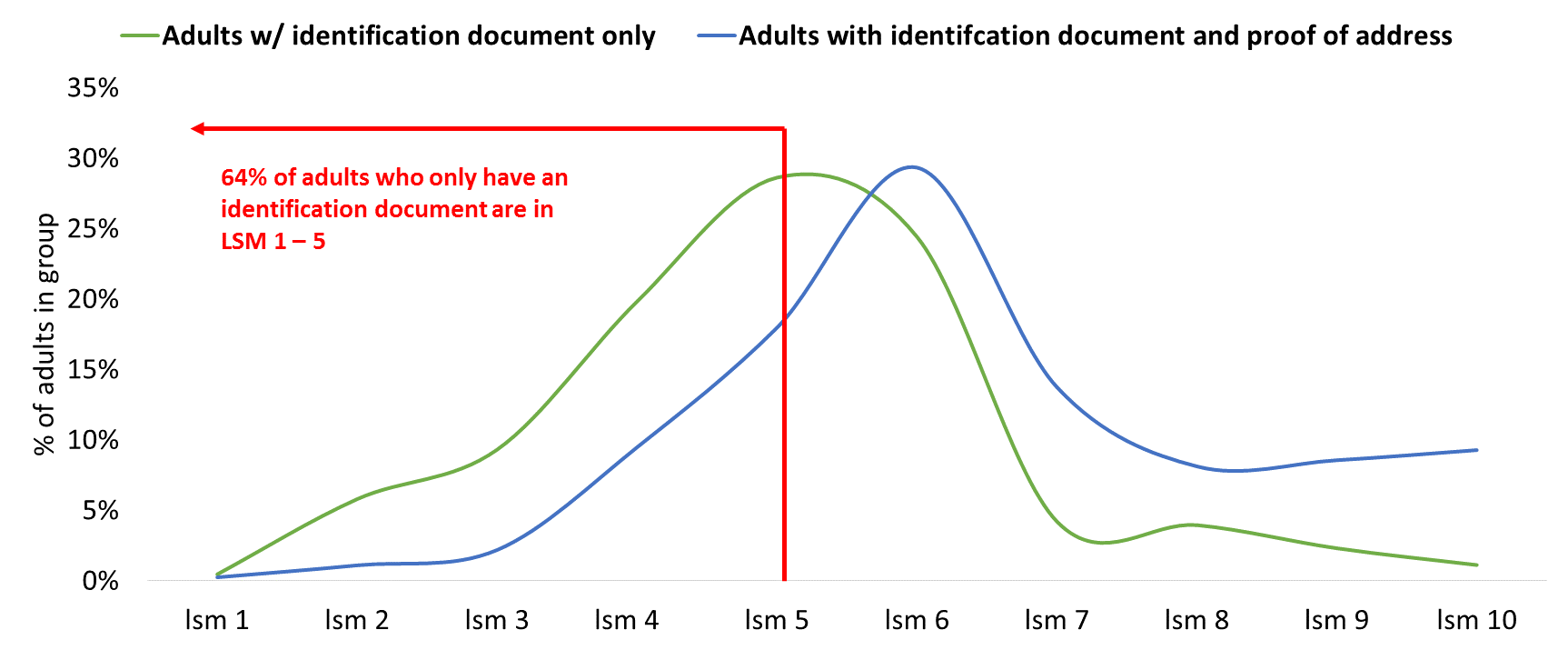

If the process above sounds familiar, consider for a moment that you are in fact part of the small minority in South Africa for which opening a bank account is relatively “easy”. For the majority of adults in this country, opening a bank account is far more onerous and time-consuming. Most adults need to go to great lengths just to meet some of the documentation requirements mentioned above. For example, FinScope, a nationally representative household consumer survey, reports that a quarter of South Africans do not have documentation to prove where they live (“proof of address”). As shown in the graph below, these adults are mostly lower income. Further, just less than two-thirds do not receive a monthly salary, leaving them without a pay slip. Lastly, most of these adults are rural, meaning on average, they live just less than an hour away from a bank branch.

Source: FinScope Consumer Survey, South Africa

Qualitative research indicates that in some cases adults can overcome these barriers by seeking alternative sources to verify who they are, such as a letter from the local chief or a religious leader. However, this can take more time, money and quite a bit of persuasion. Further, once the appropriate documents are obtained, the individual may incur additional costs for travel, and use of copy or print facilities (before even travelling to the bank branch). While a small cost or inconvenience for some, the cost is a much larger burden for many. And it’s on the brink of getting worse …

Why is this process required to open a bank account? The array of documents noted above are requested by banks in order to comply with “Know Your Customer” (KYC) or FICA legislation. KYC requirements are intended to inhibit money launderers and terrorist financiers from using banks and other formal channels. Although set by the government at the national level, such legislation is guided by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an international standard-setter mandated to “promote effective implementation of legal, regulatory and operational measures for combating money laundering, terrorist financing and the financing of proliferation, and other related threats to the integrity of the international financial system.” FATF seeks to do this through its recommendations which “set out a comprehensive and consistent framework of measures which countries should implement.” To ensure the recommendations are implemented, FATF publicly identifies countries it believes have weak measures for anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT). Once a country is labelled as weak, other countries and institutions are compelled to limit or cut ties, effectively barring access to international financial markets (something many banks and governments depend upon).

However, FATF increasingly recognises that their recommendations for KYC legislation act as a major barrier for many adults to access and use formal financial services, such as the banking system. This is particularly acute in developing countries where many adults lack documents which prove who they are and where they live. This is often seen at odds with both FATF’s aim to bring money flowing through informal channels into the formal financial system, as well as the global financial inclusion agenda which seeks to improve people’s lives through access to and usage of financial services. FATF has tried to address this.

First, in 2003, FATF published recommendations that gave room for what is called a “Risk-Based Approach” (RBA), which allows (among other things) exemptions to KYC requirements for financial activities deemed low risk. South Africa and the United States were earlier adopters of exemptions.

- In the United States, the government introduced legislation which allows banks to undertake financial services such as encashing cheques without requiring identification for transactions up to $3000 (~R 48 000) and only requiring one piece of identification for transactions up to $10 000 (~R 160 000).

- In South Africa, the government introduced legislation (exemption 17) which permitted banks to drop the proof of address requirements for transactions of less than R 5000 per day (~$315). Under this exemption, adults that only had identification documents (remember the graph above) were able to access and use formal channels for low-risk financial activity. This included 4 million adults that only have national identifications and nearly 2.7 million social grant recipients who now receive their social security grants through formal channels (as opposed to cash alternatives).

Second, in 2012, FATF introduced revised recommendations which sought to deliver a more effective AML/CFT framework. Whereas the previous recommendations permitted an RBA, the new recommendations actually require one. The likely approach that most countries will take to implementing these recommendations will be to place the responsibility for identifying, assessing, monitoring, mitigating and managing the risk of money laundering or terrorist funding solely on individual financial institutions. Under this approach, if a bank wants to introduce reduced KYC requirements for certain customers or activities, each institution must now evaluate the risk of their existing (and potential) customers.

South Africa has taken these new recommendations at full sprint in the Financial Intelligence Centre Amendment Bill 2015 (“the Bill”). The Bill, as drafted, not only shifts the full responsibility of KYC to the institutions but goes further than the FATF recommendations by not allowing for any exemptions or thresholds, even for single transactions.

While in theory, a risk-based approach should be safer and more inclusive as financial institutions are able to put more resources on higher risk activities and reduced documentation requirements for low-risk financial activities, the way in which it is likely to be implemented in South Africa risks achieving neither.

First, exemption 17 will be removed, even though this is not required by the revised FATF recommendations or guidelines. With no clear transition plan included in the bill to manage this, it is unclear what will happen to those millions of adults that took up bank accounts under this exemption.

Second, the FATF guidelines include the provision that national authorities should first undertake a national risk assessment to identify, assess, and understand the AML/CFT risks present in their country. However, South Africa has made no provision for this under the Bill. This leaves individual banks or the financial sector to identify and assess risks posed by current and potential customers without the necessary information required to develop a comprehensive view of the AML/CFT risks in the financial system. In short, banks will be faced with risks that are not well defined and near impossible for individual institutions to assess.

Banks will then need to take a decision: invest in their own risk assessment and take on the severe reputational and regulatory risk of serving existing and prospective consumers they know little about, or forego serving very low net worth clients and instead implement conservative KYC policies which protect the institution from being labelled weak by FATF or fined hundreds of millions of Rands by the regulator. An easy decision for banks.

The impact? Banks faced with severe reputational and regulatory risk are likely to close the formal accounts which were opened under exemption 17. Approximately 4 million adults and 2.7 million grant recipients may need to reapply for bank accounts under the new KYC regulation. This would undermine both the financial inclusion objectives of the government and AML/CFT objectives of FATF, as adults will be pushed back into informal, unregulated, cash-driven financial channels.

The more entrenched adults become in informal channels, the more difficult it will be to bring them back into the formal financial system. Informal systems are increasingly recognized for the value they deliver to consumers and for the sophisticated mechanisms and networks they use. They have evolved beyond the stereotype of adults transporting money over the border on foot or via a taxi. The level of service and payment options are often more efficient, effective, and customer-friendly than formal options. An informal transfer from Cape Town to the DRC can be done in under 10 minutes, cheaper than a formal transfer and with almost no administrative paperwork. Similarly, informal channels in Hillbrow, Gauteng can send funds to Zimbabwe in 6 minutes.

For customers who do not lose their accounts (those that did not rely on exemption 17), it may mean more stringent application of requirements, or new and innovative requirements from banks to know who you are (think of biometrics or worse – the new Visa regulations).

Why is South Africa doing this? It is unclear why South Africa is rushing to introduce the new legislation. It could be driven by government concern of being labelled as weak given the mounting AML/CFT pressures from other countries, and the accompanying concern that individual institutions would be cut off from international financial markets. Further, it is unclear whether or not this new Bill will indeed reduce money laundering or terrorist financing. Despite efforts across Sub-Saharan countries to reduce money laundering and terrorist financing, illicit financial flows from the region have increased 467% from 2003 to 2012.

However what is more certain is that it is going to drive exclusion for many adults from the formal financial sector, strengthening a vibrant and sophisticated informal sector. Further, as the only FATF member country in the region, if South Africa rushes to adopt the Bill, it is likely the other countries in the SADC region will follow. In these countries, the impact could be even greater as KYC documents required by banks are even scarcer and there is even less data and information available to assess the risk of consumers.

While this seems to be a small blip on the crowded radar of challenges that South Africa currently faces, it is nonetheless one that will be felt immediately. South Africa’s poorest and most marginalized adults will feel the impact first when they are cut off from formal channels to make and receive payments, including social grants. The knock-on effect will be felt when those that can still access the formal financial system have to re-submit, and likely submit new types of documentation to comply with KYC requirements. The scope of which is still unclear and may drive further exclusion from the financial sector.

However, this is not the only path. Legislation can be introduced in a way that maintains the safety of the financial system while incentivising banks to bring people into it, rather than push them out. South Africa is uniquely positioned to lead the way by adopting an approach that is appropriate, relevant, and considers the needs of people throughout the region. The choice is with the government.