Mining the gap: Financial inclusion and gender

Mining the gap: Financial inclusion and gender

23 October, 2017 •The importance of data for closing the financial inclusion gender gap.

The 2014 Global Findex Report identified that in developing economies, women are 9% less likely to be formally banked than men, with 59% of men and 50% of women having bank accounts.

The financial inclusion community is actively addressing this gap, but there is limited data available on the gender dynamics of financial inclusion that can offer insights into how to address it. However, there are some data sources that shed light on this problem and offer insight into which interventions, products and services may be particularly effective in improving women’s financial lives across the developing world, where sizable gender gaps in financial inclusion prevent women from full economic participation.

Starting with sub-Saharan Africa, this blog is the first in a series that explores financial inclusion and gender dynamics emerging from our research and the gaps that future research needs to consider.

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), 70% of women are financially excluded. More women access informal financial services in SSA than men, with 26% of women saving informally versus 22% of men. Men access more formal services, with 13% of women saving formally compared to 18% of men.

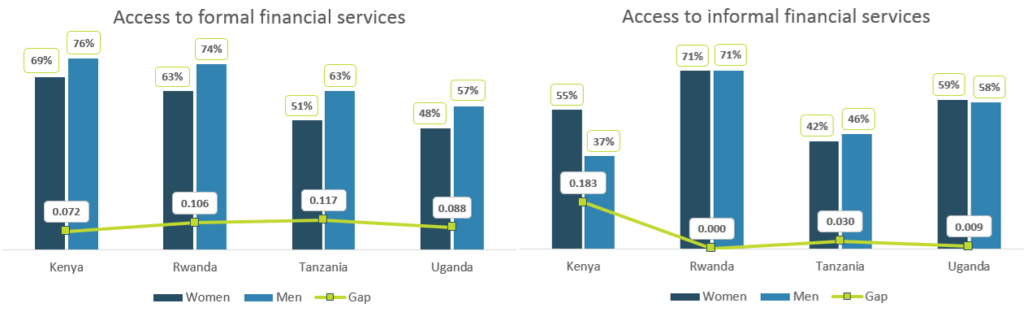

FinScope data across Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda in Figure 1 below shows that women consistently have lower access to formal financial services than men. This gap is particularly pronounced in Kenya, where women’s access to informal financial services is 18 percentage points higher than men’s.

Saving informally is not necessarily a bad thing. However, there is evidence that the informal savings mechanisms that women have access to are not necessarily meeting their needs. A study in Kenya by Dupas & Robinson (2013) provided randomised access to non-interest-bearing bank accounts among two types of self-employed individuals in rural Kenya: market vendors (mostly women) and men working as bicycle taxi or boda bodas. Despite large withdrawal fees, the researchers found that a substantial share of women used the accounts, saved more and increased their productive investment and private expenditures. There was no impact for male bicycle-taxi drivers. These results suggest that extending simple banking services to women can have an impact on women’s financial inclusion at a low cost to financial service providers (FSPs), especially compared to offering credit. However, the sample size in this study was small, and more research is needed to explore beyond the two specific types of income-earners analysed in the study.

While savings and credit have been explored to some degree, there has been limited research on insurance and the difference in risk needs between women and men. One study that offers insights is from Delavallade et al. (2015). In the study, male and female farmers in Senegal and Burkina Faso were offered a choice of weather index insurance or three different savings devices:

- An encouragement to save for agricultural inputs at home through labelling

- A savings account for emergencies that was managed by the treasurer of a local ROSCA or farmers’ group

- A savings account for agricultural input investments that was managed by the same treasurer

The study found a 30% stronger demand among men for weather insurance than among women, and among women a stronger demand for emergency savings. The demand for emergency savings could reflect the increased risk needs among women for health and childcare-related expenses. This, in turn, limits their demand for agricultural insurance coverage. For policymakers and/or FSPs trying to drive the uptake of weather index insurance products, a better approach for marketing may be to combine it with health or other emergency insurances.

One of the often-cited difficulties for understanding why women are less served than men is the available gender data. While more sex-disaggregated data is needed, it also needs to be relevant for the questions FSPs and policymakers have. For example, there are many studies on women, but for them to be relevant, behaviour needs to be compared across men and women to provide counterfactuals to interpret the insights.

Prioritising the collection and analysis of this data requires a behavioural change on the part of researchers and FSPs alike. Some central banks, such as the Bank of Chile, have already been focusing on collecting and analysing sex-disaggregated data to better serve clients and unlock new markets.

i2i is currently looking at what behavioural interventions are particularly effective in increasing the uptake and usage of financial services for women. Stay tuned for more on this work.

Brittney joined our i2i team for three months to further her insights into the fields of Behavioural Science and Fintech. She has since returned to the University of Toronto to complete her Master’s in Global Affairs.