Equal access in ASEAN – illusion or reality?

Equal access in ASEAN – illusion or reality?

22 July, 2016 •This blog series stimulates a broader discussion on gendered financial inclusion in ASEAN. We examine why women’s access to financial services does not necessarily equate gendered usage. We further explore whether the value that women derive from financial services is impacted by the provider they access them from.

It is said that if women are able to achieve their full economic potential they could add between as much as US$12 trillion to $28 trillion dollars to the economy by 2025, contributing to between 11% and 26% of GDP. Gender inequality is both a moral, social and economic issue that features prominently on the UN Sustainable Development Agenda. Financial inclusion is being increasingly recognised for its role in economically empowering women (Myanmar was the only ASEAN country not included in the report and is hence not considered in this calculation).

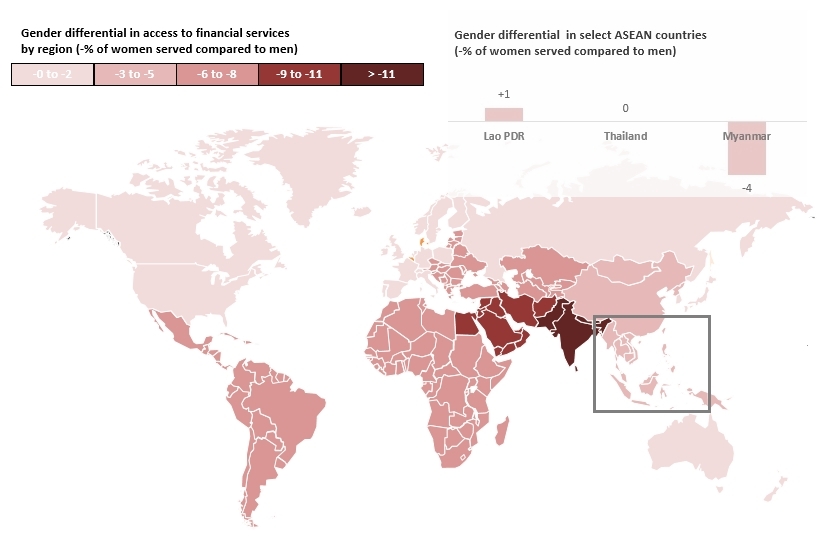

The figure above shows the regional difference in access to an account at a formal financial institution between men and women using the Findex 2014 Global Survey. It revealed that in developing economies women are 9% less likely to have an account at a formal financial institution than men. The largest gender gaps are in the Middle East and South Asia where 10% and 18% more men report access to an account at a formal institution than women. However, East Asia and the Pacific has the lowest gap in access outside of the OECD countries. Further, the MAP Financial Inclusion diagnostics conducted in ASEAN show only a small difference in ownership of financial services between men and women in Myanmar, no difference in Thailand and, in Laos, women are marginally better served. Clearly looking only at the differences in the ownership of financial products between women and men alone is insufficient to spot gender gaps in financial inclusion.

The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) global gender gap report indicates that there is a considerable difference in income earned between men and women in ASEAN. The report indicates that across the ASEAN countries, on average, women’s earnings are 70% of that of men in similar positions. Income data from FinScope corroborates this finding. Literacy rates, especially in the poorer countries in ASEAN, are skewed towards men, with 93% of men being literate and 86% of women. Labour force participation ratios indicate a similar trend. Men’s participation in formal labour is 16% higher than women.

What does usage tell us?

In order to better understand gender gaps, we have to take into consideration the degree and type of actual usage of financial services. Available data sources only provide us with a limited picture of gendered financial inclusion but frequency of usage, for example, is a good indicator of whether adults derive utility from their accounts. We know from Findex that there are high levels of dormant accounts in ASEAN: 92% of bank accounts in the Philippines and 47% of bank accounts in Myanmar did not register any withdrawal transactions in 2014.

Secondly, there might be a difference in the types of products that men and women use. Across the three FinScope countries on average, 4% more women use credit to cover living expenses than men, whereas more men use savings to cover living expenses than women do.

Thirdly, men and women use different types of providers. For instance, in some countries, women strongly prefer financial services that are owned by and operate within their local community, most of which are informal. In Indonesia, 33% of women save through informal mechanisms compared to 17% of men (FinDex, 2014). In Thailand, 35% of women borrow from village funds compared to 29% of men (FinScope, 2013). While village funds are legally formal, operationally they have more in common with informal and community-based mechanisms.

How can we complete the gendered financial inclusion picture and what does this mean for policymakers and market facilitators seeking to increase financial inclusion?

UNCDF’s SHIFT programme aims to address these complex issues; it recently launched a Challenge Fund that catalyses product innovations for financial service providers to advance women’s financial inclusion and empowerment. The programme aims to delve deeper into women’s financial access and usage patterns using both demand and supply side data. In the meantime, we ask for your feedback to inform future blog posts as we investigate the value that women get from the financial services they access.

This blog originally appeared on the UNCDF SHIFT website as part of a series on gendered data in financial inclusion in ASEAN.