Banks need a paradigm shift to make headway in developing countries

Banks need a paradigm shift to make headway in developing countries

17 July, 2015 •In 1778 the first modern-day savings bank in Germany was founded in Hamburg. The bank was set up to develop solutions for people with low incomes to save small sums of money and support business startups. Fast forward two centuries and there are now 431 savings banks in Germany with 15,600 branches and total assets of €1tn. Each savings bank is independent, locally managed and concentrates its business activities on customers in the region in which it is situated.

Financial services provided, operated and governed at the local level is not a new phenomenon. For centuries communities have pooled capital for investment, consumption and risk mitigation. In many high- and middle-income countries local provision exists in the formal financial sector (eg Germany). However, in most of the developing world, local provision is informal.

The prevailing view in financial inclusion literature is that people in developing countries resort to informal services because they have no other option. While their irregular and low income, and often distant location, make low-income adults in emerging markets unviable clients for formal providers, the majority of them prove to be regular users of multiple financial services. They often prefer informal services due to the enhanced value that locally delivered financial services provide that formal services cannot.

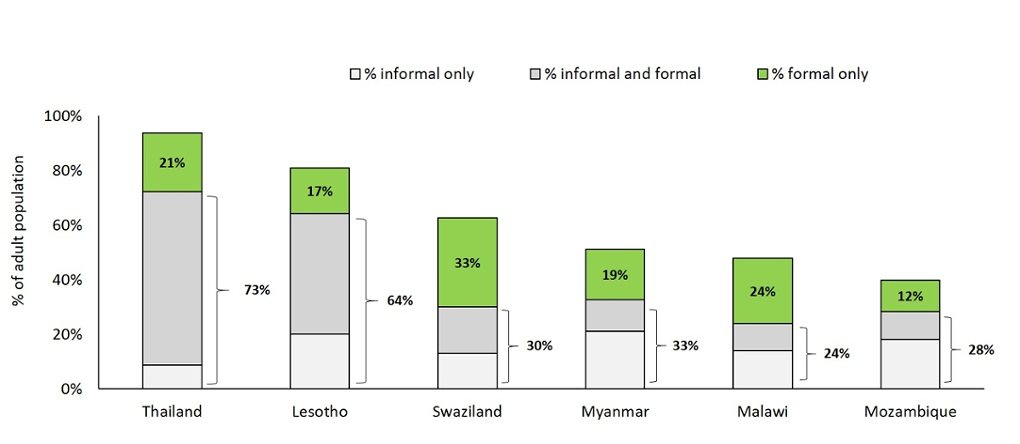

Evidence from six countries where Making Access Possible (MAP) diagnostics were conducted, provide powerful evidence that most adults rely on informal providers to meet their financial needs, either exclusively or in addition to using formal financial services. For example in Malawi, growth in informal village savings and loans associations (VSLAs) has significantly outstripped that of formal providers. Between 2008 and 2014, VSLA membership grew from 66,000 adults to 1.1 million. Over the same period, bank and active mobile money clients grew by 300,000 adults each. Even in Thailand, where 97% of adults report using at least one formal financial service, 73% of adults still rely on informal financial services to meet their needs.

Locally provided financial services are preferred for a number of reasons. Firstly, they offer users convenience and reduced travel costs, flexible services, immediate availability of funds and negotiable repayment terms. Secondly, they are not subject to the same eligibility barriers as formal providers because they rarely require formal documentation. Moreover, they are able to overcome information asymmetries cheaply and effectively through local knowledge and social networks. These collective structures are a critical ingredient of the success of local provision. For example, it provides the necessary discipline for savings groups and peer pressure for group lending models.

The result is that existing localised financial services often provide an adoption threshold for formal financial services. This threshold is overcome only when adults get greater utility from the services offered by formal providers. Providers must offer better value than informal services, mimic the characteristics that make the informal successful, or leverage existing informal provision.

The starting point for most formal providers is to offer greater value than informal services can provide. Mobile payments, with its ability to transfer value over distances cheaply, safely and quickly have been successful in this regard. In south-east Asia, low-income households have traditionally made payments over distance through informal brokers who leverage their primary business, which is not a payment service, to transfer value across distances. In southern Africa, this role has typically been filled by taxi drivers or bus drivers transporting physical cash. While the bulk of local purchases and payments is still in cash, the convenience, reliability, speed and cost of mobile payments provides better value for long-distance payments than local or informal alternatives.

The same applies to savings and credit where it may be both cheaper and more effective for formal lenders to mimic local structures. This approach is used in the group-lending schemes of formal providers such as microfinance entities. In Thailand, the government went a step further in setting up 80,000 village funds. These local funds are capitalised by the state but managed by a village committee which is often staffed by leading members of local community based saving groups, known as Sajja groups. Village funds mimic the convenience and local knowledge of the informal lender, and the savings culture of the Sajja groups. Yet, offer additional value in the form of low-cost lending and a more reliable store of value since the savings are deposited in formal banks. Village funds contribute 5% of national savings from 5.3 million adults, more than half of all savings clients. Just more than 32% of all Thai adults currently borrowing, borrow principally from them. In 2012 the repayment rates of village fund loans exceeded 90%.

Where it is not possible to mimic local services, mostly because it is too costly, formal providers may seek to leverage existing informal services. Opportunity International Bank of Malawi (OIBM) provide wholesale loans to VSLAs initiated by Care International. The VSLAs, in turn, distribute the funds to members through their existing structures. Initial repayment rates of 94% suggest a viable model for credit provision.

Where formal providers fail to adjust their offering to the culture and practice of local financial services, informal providers remain the preferred option for many adults. For example, in South Africa the major banks, following pressure from the government, introduced a low-cost individual bank account (the “Mzansi” account) in 2004 to extend financial inclusion. The Mzansi account was in essence a no frills version of existing accounts offered to middle- and high-income clients. Following the initial success of 6 million new bank accounts, 50% were dormant by 2009. The Mzansi account is no longer marketed. Most banks now offer an entry-level bank account. However, local alternatives, while informal, remain preferred amongst low-income South Africans. It is estimated that 11.5 million adults remain active users of informal savings groups known as “stokvels”.

Despite the limited success of many formal financial inclusion initiatives, the approach remains unchanged. Providers continue to focus only on the potential of technology and scale while paying scant attention to the features that make existing localised or informal provision successful. Formal providers need a paradigm shift if they want to make headway in entire markets currently dominated by local and informal financial services.

This blog originally appeared in the Guardian online global development professionals network as part of their financial inclusion blog series.