A first look at gendered impacts of COVID-19 on livelihoods

A first look at gendered impacts of COVID-19 on livelihoods

15 May, 2020 •Data from China suggests that men are more likely to die from COVID-19 than women, but the global circumstances of women (e.g. more vulnerable economic positions than men, taking on more unpaid care work) and experiences from previous pandemics (such as Ebola) tell us that the economic fall-out and subsequent recovery are likely to hit women harder than men. But how hard exactly? And what are the most pertinent areas in which we risk leaving women behind?

As we work to make sense of our current crisis and develop policies to plan for the future, data gaps are clearly a hindrance. In all fairness, collecting and reporting any data in the type of real-time fashion that is critical right now is a challenge and already makes a big difference. However, failing to consider this data in a sex-disaggregated manner puts us at a significant disadvantage. Whether we’re designing policy, putting together support packages or drawing up plans and products for the post-crisis “new normal”, considering the data in a gender-neutral manner means we’re flying blind.

This is where the collection and analysis of sex-disaggregated data on the impact of COVID-19 on livelihoods come in. The insight2impact facility has launched an innovative mobile survey to track the impact of COVID-19 on livelihoods. The initial wave of data was published on the COVID-19 Tracker website in the first week of May 2020 and will be updated with subsequent waves over the next 10 weeks. In this article, we take a first look at the sex-disaggregated headline insights for Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. In interpreting these insights, please keep in mind that the survey data only accounts for two genders (men and women), and thus doesn’t allow us to provide insights on individuals beyond the gender binary.

Increased economic vulnerability

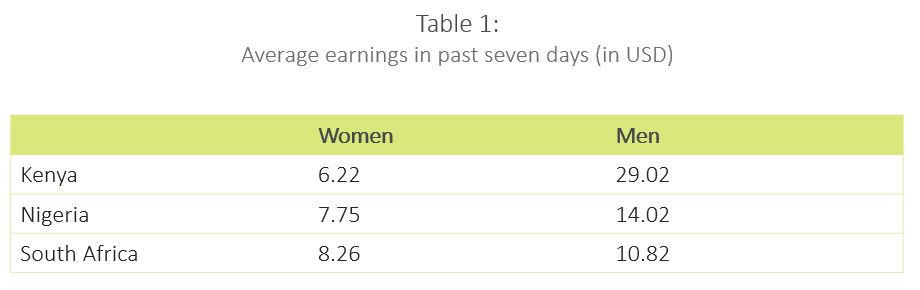

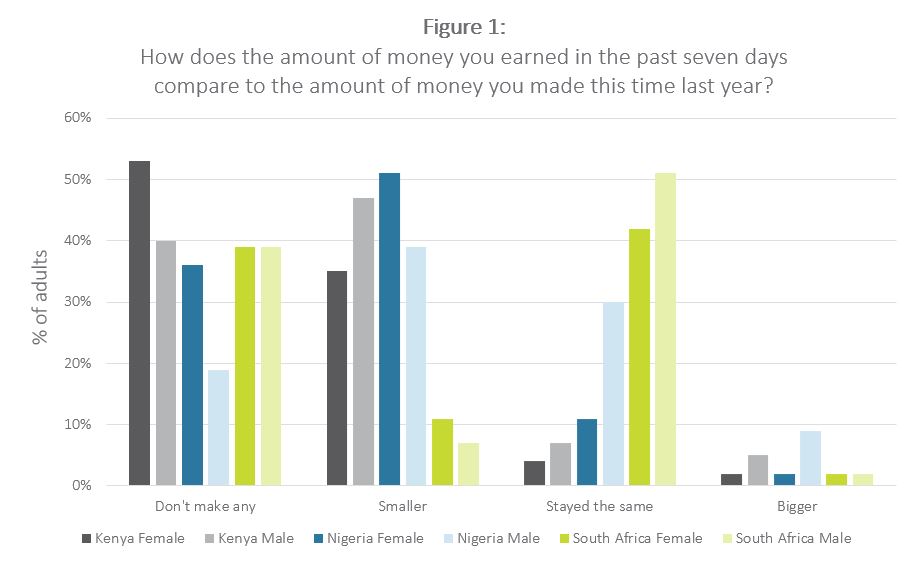

Across the board, women earned less than men in the last seven days – see Table 1. More importantly, women were more likely to indicate a decrease in their earnings compared to this time last year – as shown in Figure 1. Notably, in Kenya, over 50% of women (compared to 40% of men) indicate not earning any income at all. This tells us that women’s livelihoods – already significantly lagging behind those of men – are facing a more significant contraction and increased vulnerability.

The data shows a mixed picture with regard to financial resilience (which is a major component of financial health). In both Nigeria and South Africa, men are more likely to indicate it not being possible – at all – to come up with emergency funding in case of a sudden need. In Kenya, this picture is reversed, with more women than men indicating that they wouldn’t at all be able to raise emergency funding within seven days.

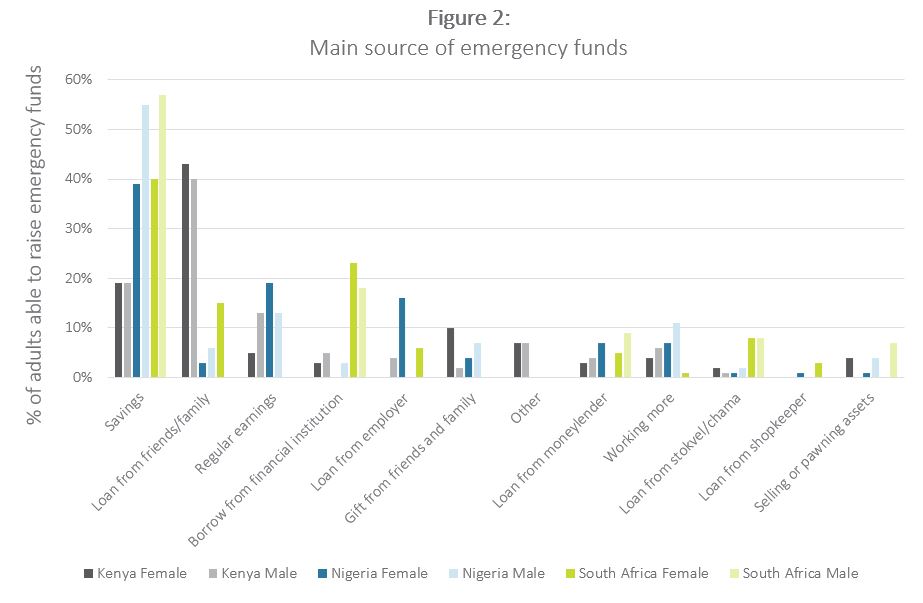

Regardless of how possible it is to come up with emergency funds, there are gendered differences in terms of the source of these emergency funds (see Figure 2). In Nigeria and South Africa, savings are the most important source of emergency funds for both men and women, even though men are more likely than women to turn to their savings. Loans from friends and family are the most common source of emergency funds in Kenya. In both Kenya and South Africa, women are more likely than men to turn to friends and family for emergency funds. Finally, Nigerian women are more likely than their male counterparts to turn to their regular earnings or, interestingly, to a loan from their employer.

Those of us who are interested in understanding how to bolster livelihoods over the next few months would do well to look at existing patterns of coping and to learn from those in the design of our interventions.

Behaviour change

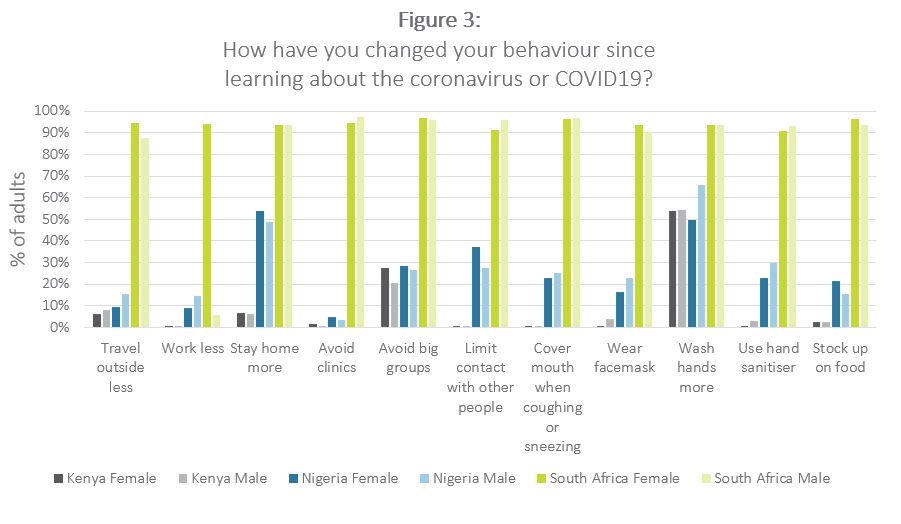

COVID–19 has not only affected livelihoods in significant ways. It’s also changing the ways we go about our lives. Mobility has ground to a halt, with the overwhelming majority of people not travelling or leaving their towns. Women’s behaviour changes reflect a greater decrease in mobility than is the case for men, however (see Figure 3). It seems men are slightly more likely to use protective measures – through wearing facemasks (Nigeria) or using hand sanitiser (South Africa) – but they still go about their lives. In South Africa, it’s notable that, while women overwhelmingly respond to the COVID-19 risk by working less (96%), this is not the case among men, with only 6% taking the same action. In Kenya and Nigeria, women are more likely than men to avoid big groups, stay home more, or limit contact with other people.

In considering the following graph, it’s important to keep in mind that South Africa is the hardest–hit country, both in terms of number of cases and stringency of nation-wide lockdown measures. This explains why South Africans across the board show greater behaviour change than their peers in Kenya and Nigeria.

These findings provide a first insight into the ways that COVID-19 is decreasing women’s financial resilience in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa and adding pressure to their income. It’s important to have figures at hand to understand how the crisis affects existing gaps between men and women, to enable the design of policy responses that do not inadvertently leave women behind. We intend to follow up by digging deeper into the survey data. It’s our intention that these sex-disaggregated insights would shine a light on the important ways in which our crisis responses need to consider the varied experiences of different population groups.

For more sex-disaggregated detail on the questions analysed, please see the following initial results.

The full dataset used in this analysis is available via the COVID-19 Tracker.

insight2impact (i2ifacility) was funded by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in partnership with Mastercard Foundation. The programme was established and driven by Cenfri and Finmark Trust.