Capitec holds true to its slogan “Its Banking Just Simpler” by removing proof of address

Capitec holds true to its slogan “Its Banking Just Simpler” by removing proof of address

19 May, 2020 •Despite the growing redundancy of the proof of address requirement, it continues to present an obstacle to the unbanked and underbanked populations who want to access formal financial services.

Proof of address has been used by financial institutions to verify the identity of clients despite it offering little value as an identifier: it’s easy to falsify, costly to verify and excludes many people from the financial system. In the current COVID-19 environment, access to financial services is even more important, however, presenting proof of address, or any form of physical identification in a bank branch comes with heightened health risks. Moreover, fraud and identity theft have been on the rise during the pandemic. Therefore, the need to identify and implement innovative and robust identification measures in the times of crisis and beyond is essential.

The exclusionary nature of proof of address

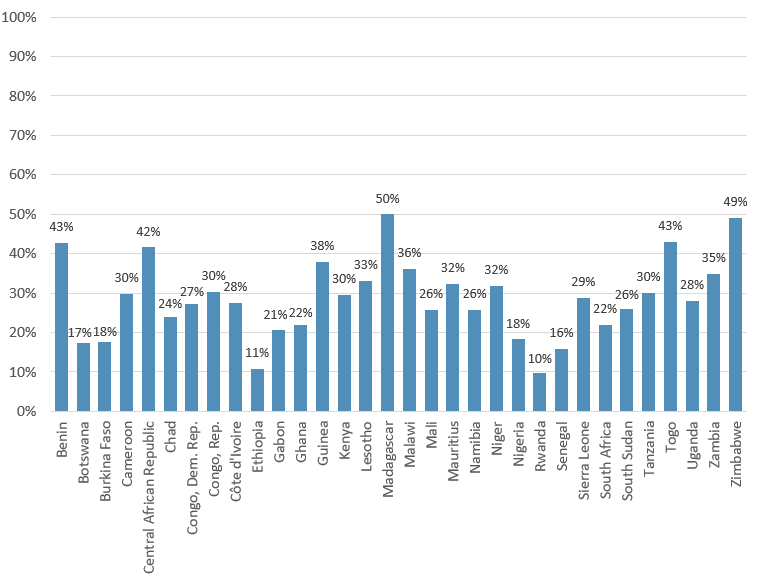

Our work across the developing world offers the explanation that banks and financial service providers are so accustomed to proof of address that they continue to use it without assessing its relevance or consequence. According to the World Bank’s Global FinDex Survey (2017), the primary reason why 29% of financially excluded adults in sub-Sahara Africa don’t have an account at a formal financial institution is because of documentation requirements. From our analysis of the FinScope surveys, we estimate that 60% of this exclusion is the result of the proof of address requirement.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an intergovernmental body with the policy mandate on countering money laundering, terrorist financing and other related threats, issued updated recommendations that comprehensively confirm that

“…countries should apply a risk-based approach (RBA) to ensure that measures to prevent or mitigate money laundering and terrorist financing are commensurate with the risks identified”. (FATF, 2012-2019: 9)

Specifically, in relation to know-your-customer (KYC) and customer due diligence (CDD) processes, the recommendation is that countries should identify customers using

“reliable, independent source documents, data or information…” (FATF, 2012-2019: 13).

This means that regulators should allow financial institutions to apply appropriate CDD processes based on suitable mitigation strategies in accordance with the level of risk posed by the account holder. The key consideration here is to manage risk by firstly understanding the risk faced and then only applying mitigation strategies in relation to that risk. Applying compliance measures that are not appropriately risk focused merely creates the impression that risk is being managed when it remains hidden or unmitigated.

Proof of address in South Africa

South Africa’s response to the FATF’s approach is progressive in its own right. FICA’s Guidance Note 7 is concerned with the transition to risk-based principles and has become well-known for its removal of proof of address as a client verification requirement. Through a comprehensive consultation phase, financial institutions were guided on how to best respond to this new outcomes-orientated regulation.

This regulation instructs FSPs to identify their clients in a manner that is proportionate to risk but doesn’t prescribe identifiers or identification processes. In practice, South African financial institutions now have the necessary creative space to implement more robust CDD identification processes that are aligned with their business practices, enabling more innovative products for their clients. This will make banking much simpler for both the consumer and the bank and more effective at mitigating ML-TF risk.

The RBA also affords financial institutions the opportunity to scrutinise the value that proof of address affords them. A forthcoming study by Cenfri revealed that the proof of address requirement accounts for approximately 60% of the CDD cost for financial institutions. We estimate that by removing proof of address from the CDD process, financial institutions can save up to 36% of AML-CFT compliance costs, which weigh significantly within the cost to income ratios that shareholders and boards strive to reduce.

Capitec’s interpretation of FICA’s amendment is an example an of an astute reaction to the new approach to appropriate risk management. In removing proof of address, Capitec has made it more affordable to on-board and process clients, and significantly expanded the margins of its untapped client base. Innovations like these are even more important during crises like COVID-19, where social distancing and strong authentication measures are necessary. The FATF recently reiterated this in a statement that encourages the use of “technology, including Fintech, Regtech and Suptech to the fullest extent possible.”

Regulatory change without institutional confidence is not enough to drive financial inclusion

Capitec’s interpretation of the FICA regulation has proven that it can be done without collapsing the integrity of an accountable financial institution. Initiatives like this one by Capitec are indicative of the scope for innovative ways to identify clients. In fact, in the process Capitec is more attuned to actual risk and can apply its resources to higher risk areas instead of meaningless compliance. Elsewhere in Africa, regulators have risen to the COVID-19 crisis with similar innovative initiatives, such as in Ghana where the monetary body amended KYC requirements on mobile money to allow citizens to use existing mobile phone registrations to open accounts with the major digital payment providers.

Despite the green light from FIC, SARB and Guidance Note 7, we have seen limited initiatives from other institutions in South Africa, while there is also uncertainty on whether Covid19 inspired KYC flexibility will be maintained post-crisis. This begs the question of whether regulatory change alone is enough to encourage innovative KYC/CDD approaches.

CDD overcompliance is a key reason for the delay in innovating

In 2017, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority became one of few to remove proof of address for the CDD processes of financial institutions. Since such changes took place however, no financial institutions have removed their proof of address requirement. The gradual transition to the RBA has revealed the impact of cultural and social barriers. A strong culture of over-compliance due to a fear of penalties means that FSPs tend to over-comply. This behaviour delays CDD innovations that benefit financial inclusion, such as removing proof of address, and in many cases results in an inappropriate application of resources and effort to ineffective, low-risk compliance activities resulting in more vulnerability to higher risk sectors.

This illustrates that it’s important for regulators and banks to work together to understand the purpose and role of new regulatory changes, particularly weak identifiers like proof of address. We expect that the ongoing hesitancy is also rooted in the fact that financial institutions do not measure the cost of compliance with AML-CFT. Consequently, there is still a significant lack of clarity surrounding the cost-benefit to both the financial institution and the client if proof of address is removed.

The future of proof of address

The removal of proof of address from FICA’s CDD requirements has made it a pioneer on African soil, while Capitec’s innovative reaction to it has put it ahead of competition in terms of the customer-experience and application of the regulation. However, the similarities between Hong Kong and South Africa strongly suggest that a purely regulatory approach to stimulating KYC/CDD innovation, such as the removal of proof of address, is limited at best. There is a need, now more than ever, for regulators and financial institutions to cooperate in introducing innovative KYC approaches which improve risk mitigation and enhance financial inclusion in a way that will have a lasting impact well beyond the current pandemic. Perhaps a starting point is to ask the difficult questions. For example, are institutions that rely upon blanketed use proof of address as an identifier effectively mitigating risk? Have proof of address requirements already transformed to become an institutional effectiveness indicator?

This work forms part of the Risk, Remittances and Integrity programme, a partnership between FSD Africa and Cenfri.