Learnings from comparing consumer credit protection systems in Pakistan and South Africa

Learnings from comparing consumer credit protection systems in Pakistan and South Africa

6 December, 2018 •For consumers to take up and use financial products, it is crucial that they trust the product and the service provider. In creating consumer trust in financial products, one of the most important building blocks is the presence and effectiveness of recourse mechanisms [1].

Understanding consumer recourse in Pakistan

The risks to consumer trust and consumer protection in the credit industry become greater as the number of borrowers and the intensity of competition among providers increase. In recent years, the microfinance sector in Pakistan has achieved tremendous growth – reaching 6.5 million borrowers[2] (representing a year-on-year increase of almost 24%) and a Gross Loan Portfolio (GLP) of PKR 239 billion[3] (USD 2 billion[4]) (a 40% year-on-year increase) as at June 2018.

In response to the risks associated with consumer protection issues, Pakistan’s national association of microfinance providers – the Pakistan Microfinance Network[5] (PMN) – is taking an active role in strengthening the grievance redressal mechanism (GRM) domain by advocating for the adoption of client protection principles at the institution level as well as at the sector level. To do so, the PMN has taken steps to a) understand what is currently happening (mapping); b) learn from peers (gap analysis) and c) implement new consumer grievance redressal mechanisms (implementation).

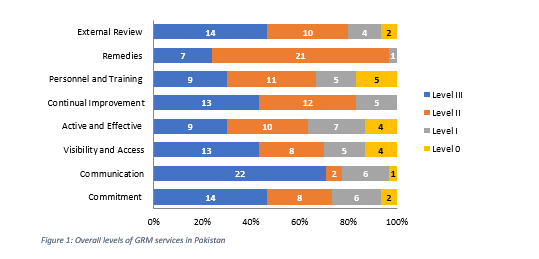

PMN, in collaboration with the SMART CAMPAIGN, developed a three-tiered GRM framework to establish minimum standards of good practice for its members. The framework outlines three levels of compliance: Level I sets the minimum standards of practice that an organisation should maintain, irrespective of its size; Level II is the intermediate level and Level III is the most advanced.

The framework gauges an organisation’s performance in the GRM domain along eight parameters [6] and sets the minimum standards that a provider should meet under each parameter. These parameters are:

- Commitment to the provision of grievance redressal channels to its clients

- Communication to clients about their right to lodge a complaint

- Visibility and accessibility of the channels to the clients

- Active and effective processes are in place for resolution of a grievance once it has been lodged

- Continual improvement of the GRM system based on client reception and response

- Personnel and training: Provider staff are well trained on how to operate the GRM that is in place

- Remedies that a provider has introduced in its products/services/systems, based on systematic analysis of the complaints

- External review of the complaints by auditors

To gauge the state of the microfinance sector with respect to GRM compliance in view of the framework above, PMN administered a survey questionnaire to its members in 2017. Thirty PMN member organisations participated in the survey, collectively accounting for approximately 90% of the market (in terms of client outreach and GLP). The survey findings show that most MFPs perform well in the GRM domain – around 60% adhere to Level III and Level II standards across all the parameters. Nevertheless, there are opportunities for improvement in practices that relate to back-end policies and procedures, training of the staff members involved in handling grievances, as well as using the knowledge attained from complaints data to improve products/services and processes. Figure 1 below shows the sector-wide levels of GRM practices, based on the self-reported scores received from the participating providers [7].

Disaggregating the survey results by size-based peer group shows that the complaint avenues offered by small and medium-sized providers are somewhat in line with the standards expected of their capacity and size. However, work needs to be done with the large providers to add much-needed sophistication to their grievance redressal policies and processes.

Disaggregating the survey results by provider type shows that the grievance redressal practices of microfinance banks (MFBs) are better than those of non-bank microfinance providers (NBMFPs), the latter of which make up 76% of PMN’s membership. Whereas NBMFPs are regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP), MFBs are regulated by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). SECP is a relatively new regulator and is engaging in the process of establishing the regulatory regime and refining the grievance redressal practices. As such, the clients of NBMFPs also had nowhere to turn to if they weren’t satisfied with the resolution of a dispute with their provider.

Overall, the study findings show encouraging trends. Most of the providers in the sector are making conscious efforts to prioritise client-centricity in their service delivery. Moreover, most of the weaknesses identified arise from a lack of capacity and the lack of formalisation of grievance redressal processes rather than a lack of will.

Learning from South Africa

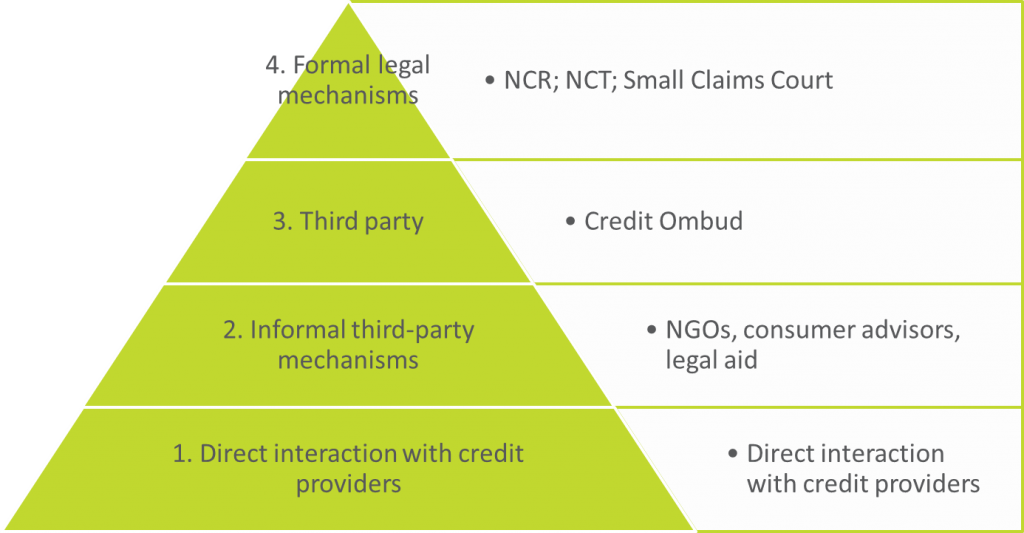

To understand more about how to address the challenges, PMN organised an exposure visit with the support of Cenfri. A diverse group of delegates[8] from Pakistan’s microfinance industry travelled to South Africa in November 2017 to learn from its credit consumer protection system. In principle, South Africa’s credit consumer protection framework has four levels, as identified in Figure 2 below[9]:

The delegates from Pakistan reviewed all four levels:

- Direct interaction: Before consumers can approach a third party to intervene on their behalf, they must communicate directly in a two-way interaction with their credit provider to raise their complaint. Most consumer grievances are usually resolved at this level.

- Informal third-party mechanisms: When consumers are unable to reach a satisfactory outcome through direct interaction with their credit provider, they can ask a neutral party to help them. Consumer advisors, legal aid and non-profit organisations (NPOs), such as MicroFinance South Africa, form part of this level of consumer recourse.

- Third-party mechanisms: Mechanisms at this level evaluate the facts and both sides’ arguments and either propose or impose a solution. The main mandate of the Credit Ombud (formerly the Credit Information Ombud) is to resolve complaints related to credit bureau information and to resolve disputes with credit providers. In 2016, this third-party platform received 14,343 complaints and enquiries and opened 4,123 disputes; in 2017, it received 18,072 complaints and enquiries and opened 4,508 disputes[10]. As such, even though it is a voluntary ombud, it is one of the main providers of alternative dispute resolution in the South African credit market.

Formal legal mechanisms: Government enforcement authorities and formal legal mechanisms such as courts form part of this level. The NCR, for example, is responsible for regulating the South African credit industry and for investigating complaints related to the credit industry. The NCR was established in 2006 (under the National Credit Act of 2005). During the 2016–2017 financial year alone, it received more than 5,000 complaints and resolved 86% of them[11]. In the process, it ensured that consumers received about ZAR2 million (USD 152,671.8[12]) in refunds.

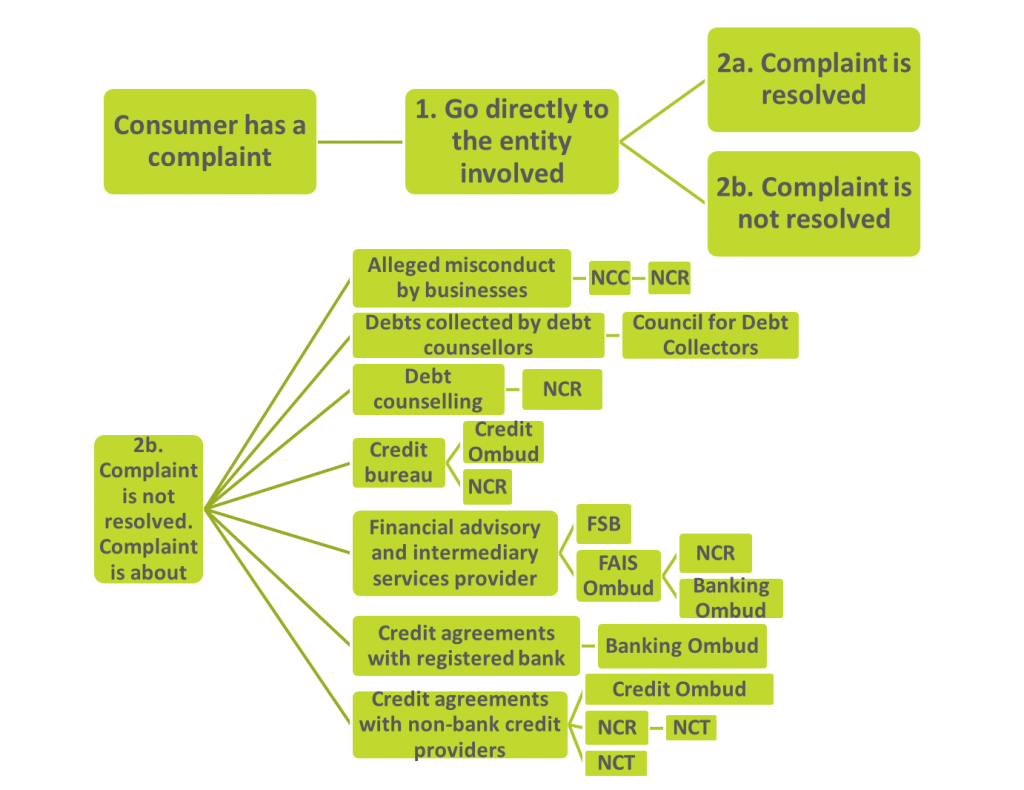

In practice, however, the South African consumer grievance redressal ecosystem is much more complex than Figure 2 above indicates. This may be a function of the absence of a single, coherent policy view over time, with multiple bodies established at the same level. Figure 3, below, represents the paths that consumers can take if they have a credit-related complaint. Depending on the nature of their grievances, once consumers have raised the complaint directly with the provider involved, they can (for example) go straight to the Credit Ombud or to the NCR or to the National Consumer Tribunal (NCT), the latter of which is an independent adjudicative entity that was created at the same time as the NCR.

While South African consumers have numerous entry points for their complaints, the complex grievance redressal system raises concerns about whether consumers are aware of, and are using, the options available to them and about whether the system is easy enough to navigate[13]. As such, this redressal mechanism may not be playing its role in creating consumer trust as efficiently as it could be.

It is hoped that the Twin Peaks reforms, which were introduced by the Financial Sector Regulation Act of 2017, will bolster South Africa’s approach to consumer protection and market conduct in financial services and that it will streamline the ombud system. These reforms involve the creation of a Prudential Authority (housed in the South African Reserve Bank) and the transformation of the Financial Services Board into the Financial Sector Conduct Authority, which will be a market conduct regulator.

The way forward in Pakistan

By comparing best practices followed internationally for credit consumer protection in South Africa – past, present and future – with Pakistan, the PMN was able to identify the following key learnings and actions for addressing consumer complaints with non-bank microfinance providers (NBMFPs) in Pakistan to augment the existing recourse mechanisms:

- Install a dedicated consumer protection cell at the regulator: To keep the process for grievance redressal simple and avoid delays in recourse due to the involvement of various entities for escalation, PMN suggests that a dedicated consumer protection cell, housed at the level of the regulators should resolve complaints, instead of having a middle tier between the NBMFPs and the regulators. The consumer protection cell housed within the regulators will be instrumental in resolving complaints that are not resolved at the individual NBMFP level and will act as the second recourse mechanism for the clients of NBMFPs. It is suggested that Universal Access Number (UAN) and email address of SECP’s consumer protection cell be displayed prominently on product brochures, in bank branches as well as on client loan contracts/passbooks and other material deemed appropriate, so that the clients of NBMFPs become aware of the recourse mechanism offered by the regulator.

- Develop draft guidelines on GRM: To improve supervision and regulation of consumer protection and to create formal buy-in from the regulator’s perspective for the adoption of GRM good practices by NBMFPs, PMN has assisted SECP in developing draft guidelines on GRM. Owing to PMN’s advocacy, in collaboration with the World Bank, SECP has prepared draft GRM guidelines (loosely based on PMN’s progressive three-tiered GRM framework) and circulated them to PMN’s members for their feedback. The draft guidelines will be formally issued by the SECP and will lay out a framework for NBMFPs to develop a grievance redressal system that is fair, transparent, accessible and efficient and that helps the NBMFPs to increase customer satisfaction, reduce operational and reputational risk and assist in bringing improvements in products, services, processes and delivery channels.

- Ensure client complaints departments are set up within all providers: PMN continues to advocate and engage with its members to set up client complaints departments where they are non-existent. In institutions where setting up a separate department is not viable due to organisational size, PMN advises organisations to have dedicated staff within internal audit or monitoring departments.

- Provide technical assistance (TA) to bring providers up to standard: PMN will build the capacity of its members by providing TA to its members to bring their practices up to par with the standards outlined by PMN, as well as the guidelines issued by the SECP, so that most complaints can be handled and resolved at the institution level. However, it is still important to have a complaints escalation mechanism in place, in case the grievances/complaints are not resolved.

[1] See Rinehart et al. (2018).

Figure 3: Credit consumer complaints process

[2] See MicroWatch (2018), a quarterly publication by PMN.

[3] Ibid

[4] 1 USD = 118.5 PKR (average exchange rate for 2018)

[5] Of the 50 microfinance providers in the industry, 46 are registered members of PMN.

[6] Using a set of 16 indicators

[7] An additional compliance level, “Level 0”, was introduced to capture the outliers in case of non-compliance with any of the three levels.

[8] The delegation included representatives from PMN, MFBs, NBMFPs and the SECP.

[9] See FinMark Trust (2007).

[10] See Credit Ombud (n.d.) for its annual reports.

[11] See NCR (2018) for its annual reports.

[12] 1 USD = 13.1 ZAR (average exchange rate for 2018)

[13] See National Treasury (2017).